No Fear No Die (1990) dir. claire denis

Claire Denis, a fixture in French filmmaking, is no stranger to the topic of the postcolonial world or at least colonialism’s retreat and retooling into a more silent puppeteer: out of sight, out of mind. In her third feature, No Fear No Die, her crux is more subtle and less in your face than her debut, Chocolat, but just like her subject at hand, just as effective and just as damning. Denis takes a more allegorical approach, using the vessel of Cockfighting to display societal dynamics. The duo of Dah, a Beninese immigrant, and Jocelyn, a Martinican immigrant, hatch up a chicken-fighting scheme with a predatory white businessman, Pierre Ardennes, who had, as he crudely asserts throughout, dealings with Jocelyn’s mother. Denis meditates on black masculinity, the inherent capitalistic battle between craft and commodification and the illusion of freedom fed to oppressed peoples under the constraint of “less visible”, but alive and thriving colonialism.

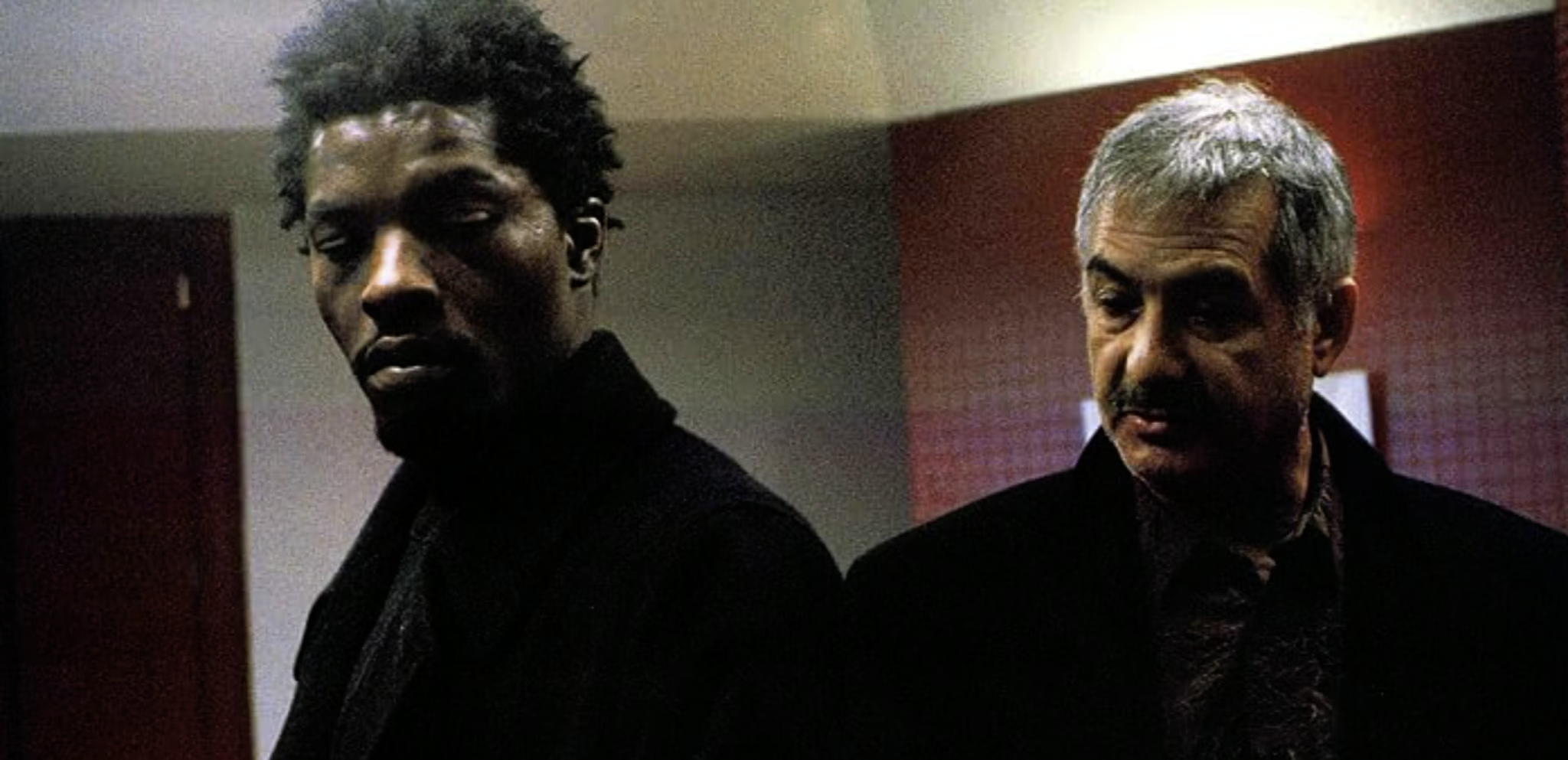

From the initial meeting between Dah, Jocelyn and Pierre we observe an unspoken standoff. Pierre props himself up as a friend, mentioning how he’s come a long way and has made accommodations for them, before trying to sweeten up his side of the deal. Throughout, Pierre acts as if he is doing them a favor despite Dah and Jocelyn providing a valuable service. Dah stands his ground, insisting terms previously agreed upon remain ironclad. This chest-puffing remains throughout, materializing in different ways. Pierre’s futile attempts at small talk met with brooding silence, Pierre’s sneaky verbal belittling, calling them boy or son, and Pierre’s digs at his past with Jocelyn’s mother, insulting her and him slickly (and later, more overtly) at every chance. Dah’s insistence on terms no matter how slyly Pierre tries to undermine them (whether that’s paying them upfront two francs short or asking them to help with the construction of the pit) and Jocelyn’s forbiddance of Pierre touching his birds, slapping his hand a way and grilling him at every attempt. In one scene, Denis places Dah in a doorway, standing strong and straight as Pierre and his stepson have to navigate past him to leave, making themselves small, Dah’s smile creeping in, aimed at Jocelyn upon their departure. Racially charged masculinity is centerstage, and that’s before investigation into the act of chicken fighting. Calling the chickens their cocks throughout, Denis has set up the perfect pissing contest. The metaphor isn’t hammered on your head but made clear in poignant dialogue. Jocelyn while caressing his birds, states cheekily, “They’re as bushed as me”. Dah constantly asserts “Men, cocks, same thing”. There’s this particular envy that accompanies this cockfighting on both sides. Dah and Jocelyn envy Pierre’s lifestyle: what he has, his money, his wife. They seek to obtain it for themselves. As they meet Pierre at his work in progress pits Dah comments “I bet this guy is really raking it in” in awe of his property. Toni, the white, blonde haired wife of Pierre, is sought after as if an object, a prize to achieve, to destroy, a revenge for both Jocelyn and his mother. She becomes a twisted fixation for Jocelyn, watching her in short stares, naming a white chicken after her, and lashing out at her in the climax. It’s not romantic; its a masculine urge for revenge, to make ugly like Pierre’s done to his birds, to ruin something his oppressor finds sacred, to do what’s been done to his woman, his mother. This is displayed when Jocelyn grabs the chicken named after Toni by the neck in front of her as if to choke her by proxy. Meanwhile, Pierre’s stepson is jealous of Toni’s curiosity towards Jocelyn, Dah and their birds. He sees them as a threat, thieves come to whisk Toni away from him. He jabs at her when she takes interest in the birds, mocking her, saying “you tuck them in now?” before trying to force intimacy on her. Later, he asks if he must “dye [his] dick” to get some from Toni. Denis gives this cockfight the proper depth it requires. And the end result is violence by way of stabbing, the action of inserting one into another. A true cock fight. A fatal cock fight.

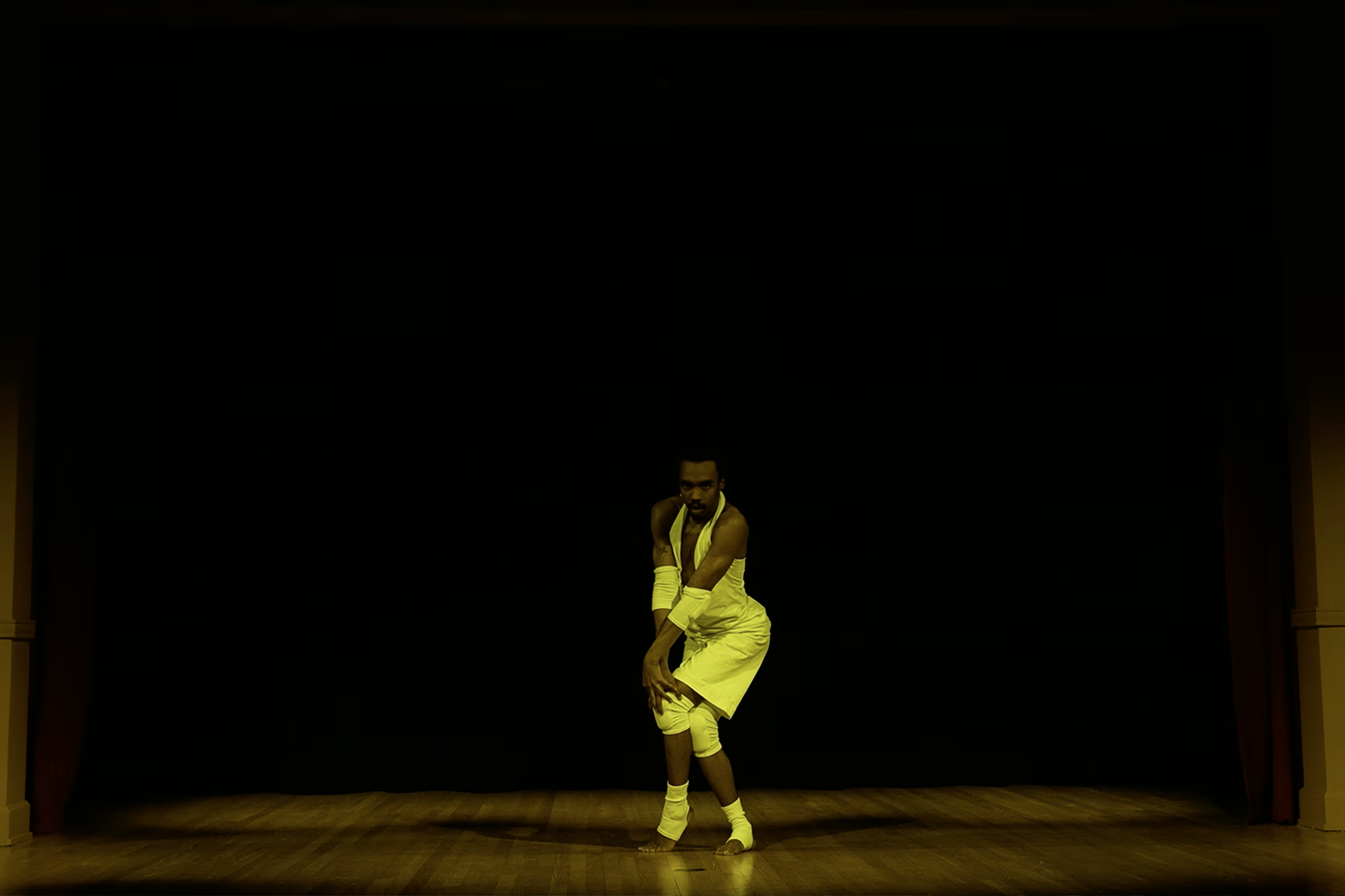

Jocelyn, taught the craft of chicken fighting by his grandfather back home in Martinique, is extremely attentive to the birds. Dah describes his preparation as a “ritual”: he starts everyday at 7am, makes sure Dah has bought the proper vitamins for them, plays the same repeating rap song while training, feeds them the exact same amount, sheds them at the dinner table, diligently gives them haircuts, fasts with them before fight day, rubs them with spittle, and tends to them after their battles. Jocelyn shows great care towards the chickens, unlike everybody else who view them as means to a profitable end. He sees in them a real beauty and Denis treats them as such. She utilizes long process shots of Jocelyn’s training and static shots of the birds allowing us to take in all of their regality. Jocelyn insists Pierre knows nothing of the birds, arguing that the carpet in the pit is shit, and insisting they use horns instead of real knives, despite the demands for blood from the spectators. Whilst showing Dah and Jocelyn around the place he seeks to have this chicken fights, Pierre insists, despite Jocelyn’s protests, that “there’s stacks to be made!”. Pierre seeks to commodify the chicken, not caring about their beauty or being as long as his bottom line remains unscathed. Dah shares his dollar signed stained eyes, urging Jocelyn to acquiesce to Pierres wishes. This battle ensues as Jocelyn tries preserve his birds, attached to them emotionally, spiraling as he watches his integrity compromised for Pierres demands. Whose dick is bigger: the artist or the businessman? Who will give in first? The artist must adhere to who pays. Denis’ chicken fighting serves as an example of profit and passion intersecting, passion usually taking a backseat. Before spiraling, Jocelyn pleads with Dah to split, after they’ve got a bit of the money, realizing the working relationship is untenable and predatory in nature. Dah refuses lusting after the potential financial gain. We watch as Jocelyn suffers under the weight of capitalism, being undone slowly, turning to the bottle when his art is ripped from him, pimped out for pay. The chickens, in line with the metaphor of masculinity, also represent black bodies, exploited for capital, as sources of awe to be destroyed for entertainment, discarded and digested. This culminates in the dynamic final act as Jocelyn accuses the money holding, bet making, expletive screaming crowd of being vermin, pigs and dogs, relishing in the violence of his precious birds, getting off on their blood, on the destruction of a beautiful being. The black body is a commodity to use for pleasure. Pierre states that just like his mother, Jocelyn is “good in bed but born to lose”.

Pierre grants them a small box in the basement for their living quarters, away from the patrons of his restaurant, freezing cold. It’s not a space made for humans, emphasized by Denis’ claustrophobic visual language: lots of Close ups and medium close ups, lots of framing within frames by doorways. When Jocelyn protests that there is no shower Pierre declares they have to use the staff ’s shower to wash, stating Jocelyn has no use for shower anyway, that his mother had to “wash [him] by force”, a jab at his West Indian culture and an accusation of being uncivilized, dirty and primitive. Despite their service they must always enter through the back of the establishment no matter if there are patrons or not. In one scene, Dah comes bearing cigarettes for Francois, the black chef, and is told that he can’t come in through the front door. Dah reveals that Jocelyn has a debt he hasn’t paid, which informs them entering this agreement with a character they know is immoral. Dah states plainly they knew what they were getting into, a deal with the devil, out of necessity, to progress. In another scene, Pierre locks them in the restaurant to force them to use knives for the fighting. This denial of exit is clear parallels to the black illusion of mobility under capitalism in a “postcolonial” world. Dah must constantly remind Pierre that this is a partnership, that he is no wage slave like the chef whose character serves as juxtaposition. But if he must keep stating it, is it true? Denis has them play the scratch off lottery and lose, a small, seemingly insignificant moment which encapsulates what she poses: Progression in an antiBlack world is always a long shot gamble for a black person, a pipe dream sold to black people to continue to strive for instead of burning the whole system to the ground.

Throughout, Claire utilizes cinematography so rich and easy on the eye yet so subdued. It never calls attention to itself, yet it’s drenched in such jaw dropping beauty. She deploys warm tones to perfection: you feel the heat. The music is relevant: Buffalo soldier plays repeatedly, the words “stolen from Africa brought to America” echoing in your head. Bankole and Descas are everything in their roles, swagged out but with meaning to boot and they carry it in every action, every word. For me, No Fear No Die is an impactful first impression to Denis’ work. Having watched three times in the span of a week, this film has been seared into my brain. Dah’s last words over Jocelyn are perfectly put: “He lives amongst his cocks. All he has now.”

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.